Having An Opinion Is Part Of The Fun

My friend Joseph was thinking of selling a couple of medium-format cameras recently. His kit seems to change regularly as it follows the ebbs and flows of his enthusiasms. Personally, I try not to think too much about the hardware because I find it distracts me. Plus – the solution to the creative problems we come across in photography is seldom technical. But I had been thinking about medium format for a while and from what I understood the best value for money out there is generally seen to be a Bronica. So that is what I was vaguely considering until Joseph mentioned that he was getting rid of his Hasselblad.

So I borrowed it. What better way of deciding whether it is good for you or not? Joseph came round and we sat in my garden in the sunshine and he talked me through the basics: how to put the film and take it out (obviously) and one or two idiosyncracies of the model. You wouldn’t call it a big camera but it has a certain presence in your hand, a weight and a bulk that is entirely different from the kind of smaller kit that I am used to. And one glance down into the magical garden of the viewfinder convinced me that this was something truly different. There is a kind of 3D effect that draws the eye in to what seems like another world – an effect enhanced by the reversal of the image in that small square.

Medium format is not that cheap when you start adding it all up. At least 50 pence to buy each negative on the roll, the same again for developing and same again for scanning. So some £1.50 or more per shot. It goes against the grain then to waste it by shooting more or less anything just to find out what it looks like. At which point – enter Steve who had come round to my house to do some building work. He was sitting in his van one day and the framing of the van door and his posture in it just made me think of the Hasselblad so I shot inside to get it. The photo above is the result.

I have to say that I was pleased with it. I shouldn’t praise my own work of course, but it has a simplicity and balance that to me is part of the essence of a good photo. Plus it is recognisably a black and white Steve. Colour just isn't the same for portraits. There is only a partial recognisability which I think comes from an instinctive misreading of colour in the photo. For a split second we know it is not real and then a cultural reading takes over and we ignore that concern.

So, I patted myself on the back: “Nice photo!”

A little while later Steve’s wife, Pam, was also round at the house. For some reason the photograph was mentioned and I offered to show it to her. Out came the laptop and I pulled it up onto the screen and then sat back modestly and awaited her cry of joyful recognition.

And waited. There was complete silence for several seconds and then she spoke one word.

“Jowly”, she said.

I looked at the photo and then back at her. Jowly? What about the simplicity? What about the balance? I sought to shift her view by pointing them out to her. She looked again and shook her head: “Jowly” she repeated.

It was a difficult moment socially as she, Steve and I sat round the laptop. There was nothing to be done I concluded. The unstoppable momentum of my creative vision had hit the immovable buffers of her opinion. We shuffled our feet uncomfortably for a few moments and then passed on to other things, the photo forgotten.

It's great that photography is so approachable. Because, while few people other than those who take an interest in such matters would venture an opinion on a sculpture or painting or other work of fine art, virtually everyone feels confident in venturing an opinion about a photograph - especially when the subject is familiar to them, whether it be place, person, view or whatever.

Pam didn’t like the photo because it didn’t reflect the Steve she knew. I liked the photo because I thought it contained certain characteristics that I value in a photograph. That instant engagement is so refreshing. You can change your mind every day if you want. After all, it's only a photo.

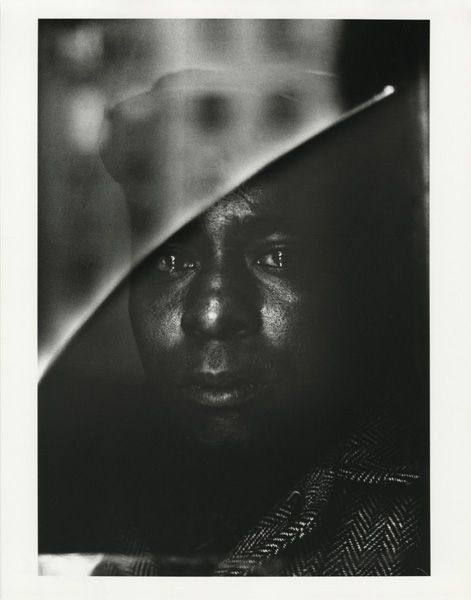

Below is Malcolm, Steve’s mate (in the professional as well as the social sense). Unfortunately, we’ll never know what his wife thought of the shot because she didn’t come round that day. Maybe she'd have said: "How come you got his ears in focus and not his nose?" Hmmmm....... #workingonmyhasselbladtechnique