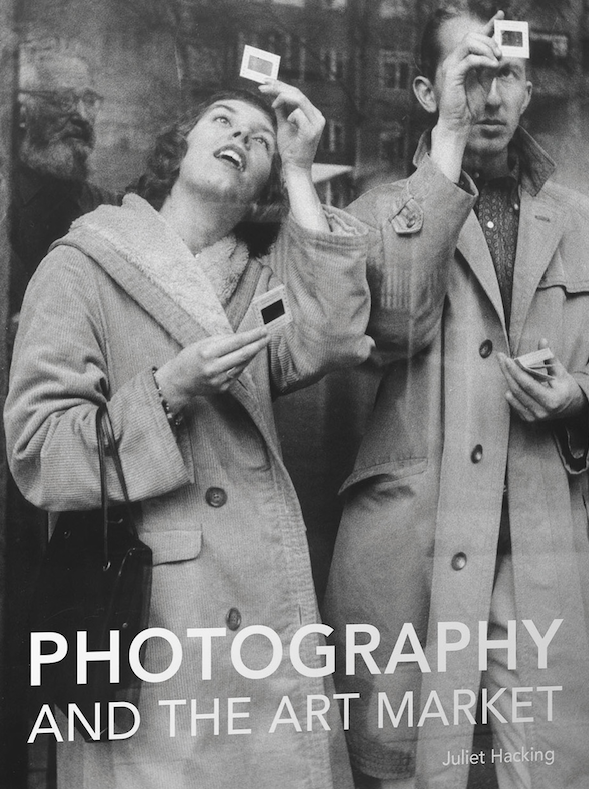

Here is an interesting book.* For £30 you get a handsome 266 hardback pages by the Programme Director of the MA in Contemporary Art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art. She was previously Head of the Photography Department at Sotheby’s auction house and therefore has much experience of the book’s subject – how the art market for photography functions.

The book is divided into two sections. The first is aimed at potential collectors and deals with how to navigate the market for art photography. It starts off at worm’s eye level but soon enough rises to the aspirational. If you were thinking of starting off a photograph collection then it would be pretty essential reading. There is detailed advice on establishing authenticity, researching value, analysing auction reports, and recognising pitfalls. Some of this works on a pretty big scale. For example, there is what Dr Hacking describes as ‘rebranding an alternative investment portfolio as a curated collection.’ Here is what you do. You promote a Fund (that is, you interest both private individuals and institutions with the right kind of money) and go scouting for reliably valuable photographs, hoovering up whole collections along the way and attracting more investors as you go. With a wave of the wand, Investment Portfolio becomes Collection in its own right when you start persuading influential people to talk it up, you sponsor serious exhibitions in which it features, you promote academic conferences which highlight it and you even publish catalogues dedicated to your Collection. Having maximised your brand you then “bring it to the market” and if your timing and technique are right you should have generated such a frenzy that you will make many times what you have spent in putting the brand together. The author says that the knack for “successful monetisation” is to “conjure up aura”.

It is Dr Hacking’s main theme that the market is crucial to the making of Art (as opposed to art) and the second half of the book addresses that theme: how photography (or some photography anyway) became Art and therefore became very valuable. Dr Hacking’s argument is that there has always been, from the very beginning of photographic history, a distinction drawn between Art-as-photography and photography-as-art. Few would argue with that. The former is what artists do and the latter is what photographers do. There is overlap and there are grey areas: for example, in Sotheby’s, Robert Mapplethorpe has been sold as an artist in London but as a photographer in New York. Traditionally the reverse has been more true, however: those who are big in photography may be unheard of in contemporary Art and vice versa.

Dr Hacking’s survey of the market history of photography makes clear that until well into the second half of the twentieth century it was difficult to get any sort of a decent price for a photo. But as the value of older art went into the stratosphere, photography helped fill the market gap that was left. Between 1975 and 1991, for example, photography prices increased by some 680%. Then when contemporary art began to take off at the beginning of this century photography had to try and hang onto its coat-tails. By the 21st century six figures for a photograph was no longer exceptional but 99% of all sold photography still falls outside of the contemporary art market and therefore the really, really big prices.

So, if there are these fairly simple economic arguments about supply and demand then how is it, we might ask, that the market can impute cultural value? Surely, the price paid is a result of that very cultural value and not a determinant of it?

What enables an image to arc across the photography/Art electrodes is a complex institutional circuit, according to Dr Hacking, the wiring of which encompasses critics, dealers, writers, specialists and institutions. In essence, Art photography is whatever this coterie decides it to be – its nose being guided by artistic pedigrees, track records, market history and personal opinion. This does seem a curious argument. It must lead ineluctably to the conclusion that there is no intrinsic quality in the picture itself which makes it Art. Good, bad or indifferent – it makes no odds. It is simply the opinions and prices which trail in their wake. Taking the example of Andreas Gursky’s Rhin II – sold for over £3 million several years ago which was then a world record price for a photograph – you might well conclude that it is indeed a pretty mediocre image. But the rub is that everything points to its being a very safe investment vehicle.

Like all circuits, the one described by this book might be seen as ending at its own starting point. What underpins it, that cultural value is determined by price and price is determined by cultural value, may well be true within the walls of the auction house, but it is not necessarily so outside them. It is also an argument which has an interesting parallel with banking until 2008: that was another world in which a group of people considered themselves to be too expert by half - and look where that ended.

Towards the end of this book the author says that we should be asking not why Rhin II is so valuable but how it has come to be so. Indeed we should, because this Foucauldian question inevitably leads us onto the issue of discourse. Viewed from this angle we can see that the book is not so much a commentary on that discourse as part of the discourse itself. The first half is after all a scholarly explanation of how the market functions and the second half is a scholarly account of the history of art photography based on an examination of historical values. By its very nature it is an account for participants of all kinds and its advice will influence behaviour.

Perhaps surprisingly, there is no comparison in the book between the photographic commodity market and any other enthusiast-based commodity market. For example, in the historic vehicle market (where Art is not in issue) prices in the last fifty years have also gone through the roof. If a graph of comparison showed significant similarities in its peaks and troughs with those of the photography market then we might well conclude that it was overall macro-economic factors that affected value as much as judgments about Art. Put bluntly, the quality of what is being bought doesn’t matter so long as the commodity can deliver a return. One of Lawrence of Arabia’s series of old Broughs, for example, is always going to maintain value even if that marque’s rear cylinder did overheat with monotonous regularity.

The book is a good read. The prose is clear, the annotation copious and the author’s pedigree impeccable. If you want to be a collector you had better read it. Even if you don’t, its market-based view of photographic history is, I think, a first and, whether you agree with it or not, it is very interesting food for thought.

*Photography And The Art Market by Juliet Hacking (Lund Humphries, 2018)