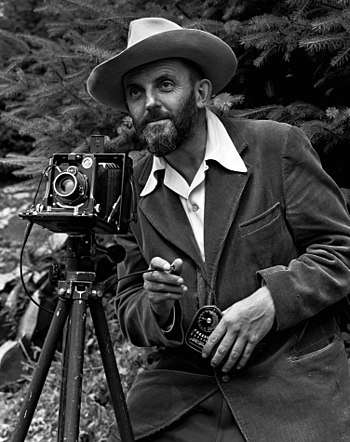

I happened across a copy of Walker Evans’ ‘American Photographs’ in a charity shop for £3.49 recently – which seemed like a good deal. According to a MOMA essay it is “still for many artists the benchmark against which all photographic monographs are judged”. I’ve never quite understood why, though: I can see its value as a historical document and as Evans’ attempt to set out his stall photographically speaking as a documentarist; but so many of the images, especially towards the end, seem a little lacklustre. I turned to the standard Photo encyclopedias – Frizot, Marien and The Oxford Companion, and none of them seems to take a standard view. He does get two mentions in Honour and Fleming’s ‘World History of Art’ however and having browsed the book and the internet (where there is a terrible lot of gushing prose) a bit more I think that probably his strength was in making straight no-nonsense photographs of socially important matters. This doesn’t necessarily make for particularly eyecatching photographs but if you hang on in there a certain homespun ordinariness does emerge even if it is often at the expense of visual interest.

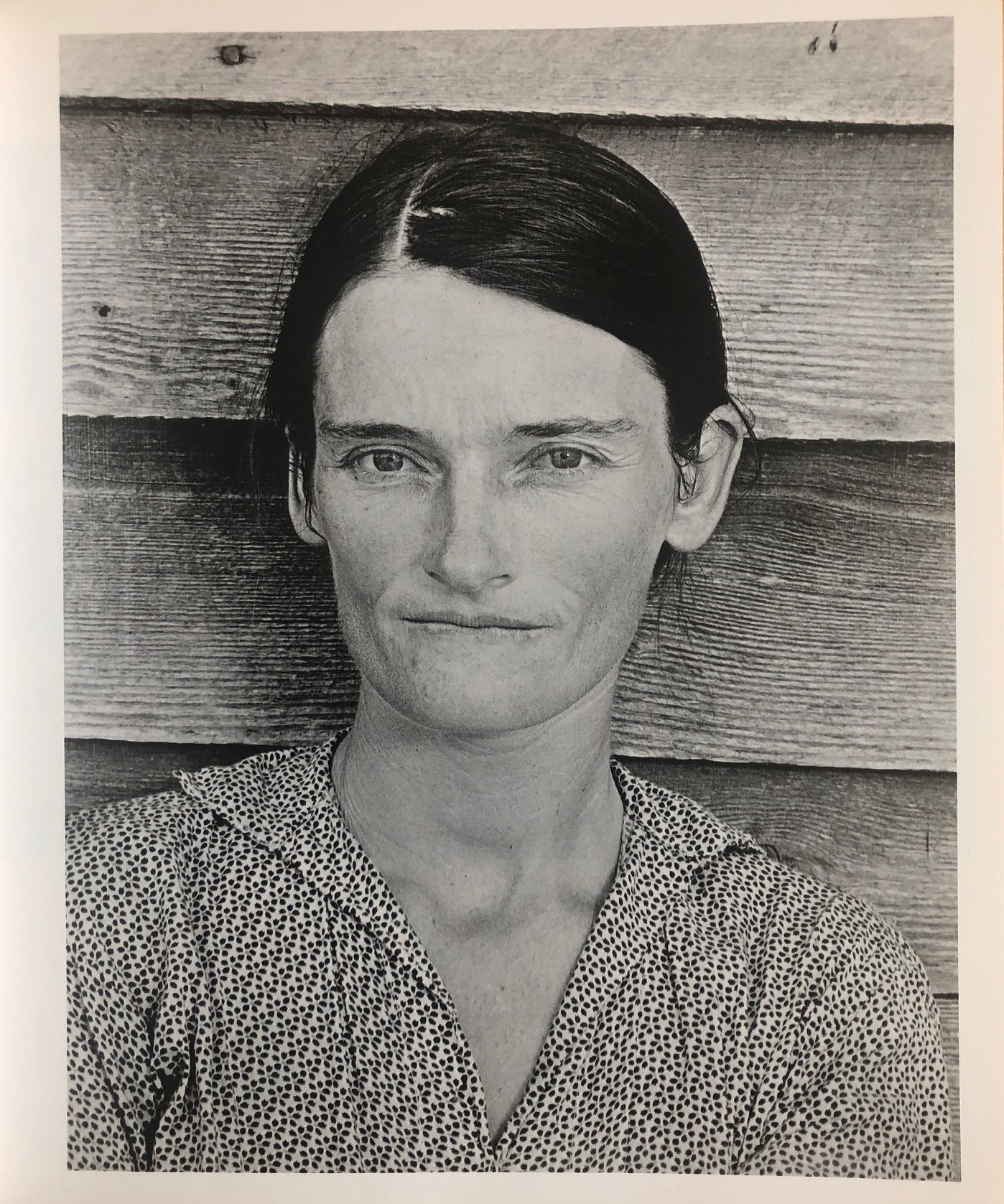

The very well known photo below set me thinking.

“Alabama Cotton Tenant Farmer Wife” is the title in “American Photographs” but it seems to be better known now as ‘Ellie Mae Burroughs’. Taken on my iphone from my copy of “American Photographs” 1988, © Museum of Modern Art, New York.

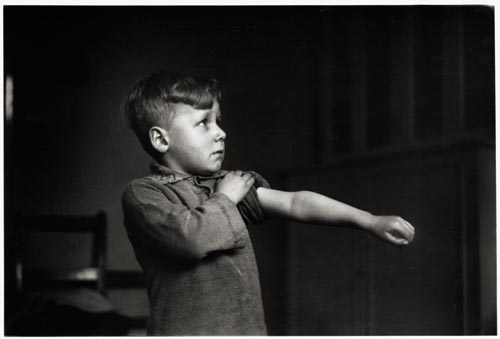

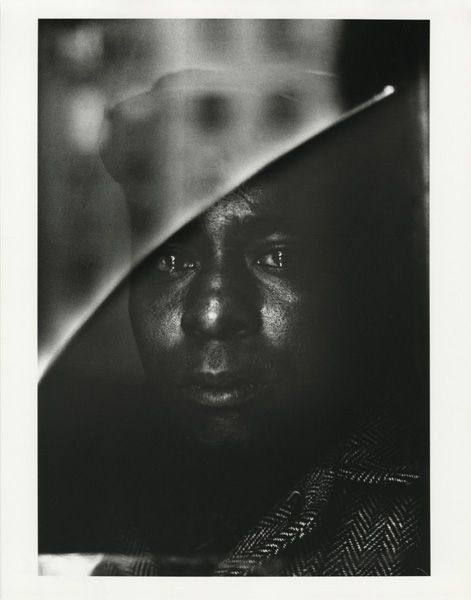

Why is it, I wonder, that portraits of otherwise anonymous subjects always stand the test of time better than those of celebrities of the day? Here is a shot by (the very great) Jane Bown of Edith Sitwell in 1959. Which of these two photographs has more substance now?

Dame Edith Sitwell, 1959 by Jane Bown and taken with my iphone from my copy of “The Gentle Eye: Photographs by Jane Bown” © The Observer 1980.

Celebrities, I suppose, have an expectation of being recognised. That, after all, is why they are being photographed and it shows in their minor performances for the lens. The Common People have no such expectation and maybe that is why, as subjects, they have a certain timeless quality: their importance was local, not global, and is unaffected, unlike celebrity, by the passage of time.