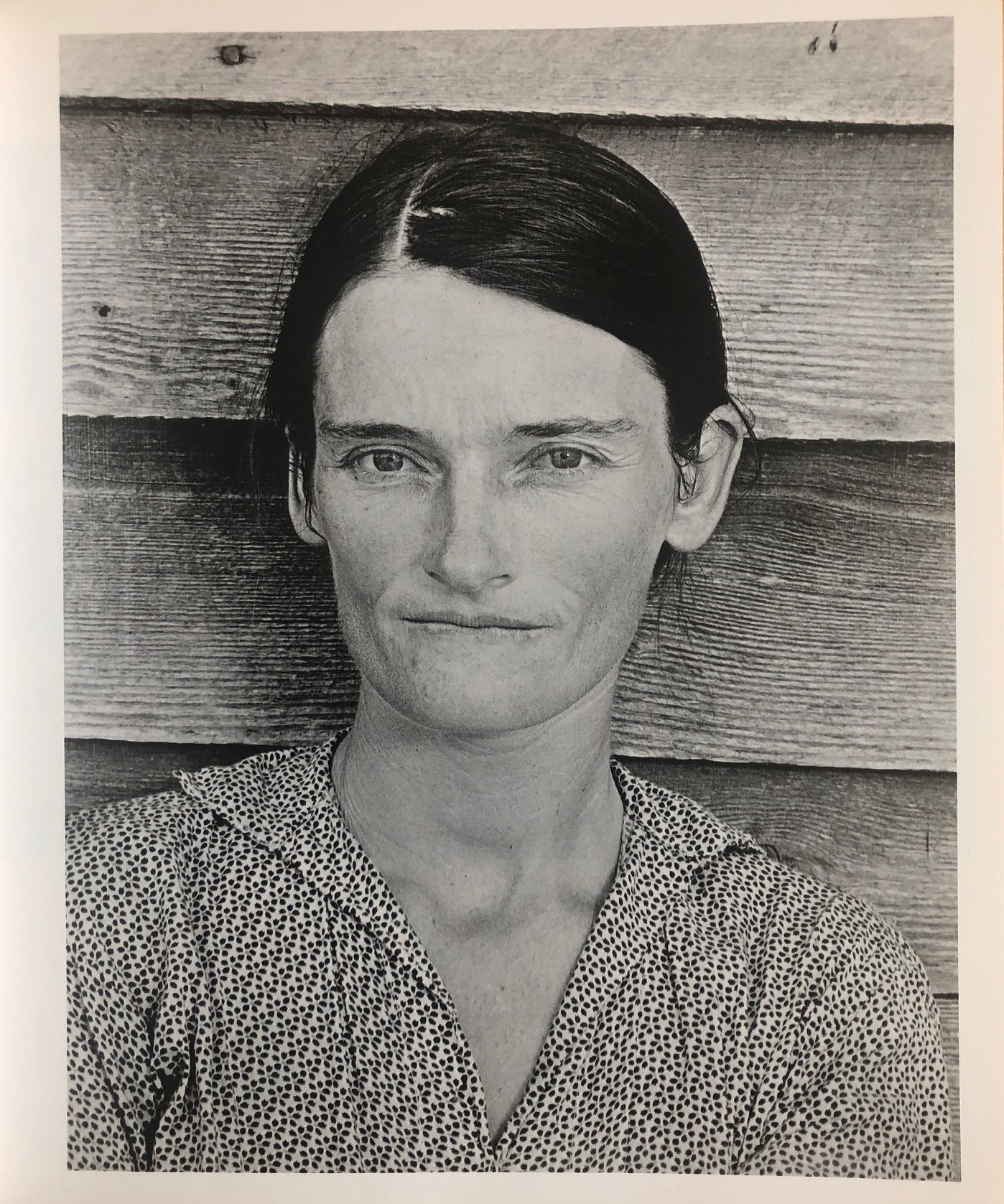

Bromholm Priory, ruins of Chapter House wall.

If you have the time and means to nose around the backwaters of the UK you will generally come across something of interest sooner or later. You might need a map, and you will definitely need a sense of curiosity and an open mind, but you will get there.

Recovering from a shambolic lunch in a Norfolk café this summer (howling dogs, bizarre salads and bickering staff) I set off on a walk round the coastal village of Bacton to clear my head. A workman trimming hedges stopped to let me pass and as I turned to get past him I saw, a couple of fields away, the magnificent ruin above. I asked him if it was possible to get closer to it. He told me that it was part of an old monastery, now on a working farm; that he and his pals had played there as children; that a new farming generation had banned them; but the very latest entail holders seemed not to mind visitors. So I marched up the drive to a kind of Gormenghast Hall in a deserted farmyard and rang the bell. Nothing. I rang again. Shuffling of feet. Door opens. Darkened hallway. Young man. Could I look at his ruins? Sure, he said, and shut the door.

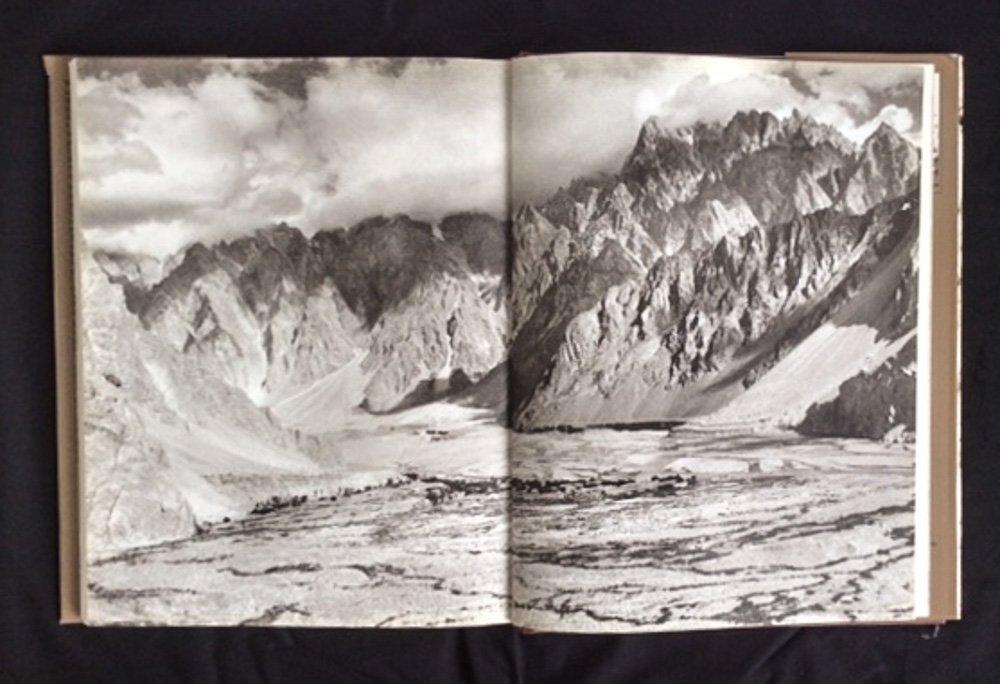

Bromholm Priory, ruins of refectory wall.

So - I looked. There wasn’t much to see bar these walls and some unkempt farm buildings and machinery but that just stimulated my imagination all the more. All around me stretched the big East Anglian skies and flat landscape. The sea was only a few fields away. A shower of rain fell. The wind blew. The atmosphere was breathtaking. Something ineffable pulsed for a second and then was gone. I stared through the Hasselblad’s ground glass and clicked several times. Then suddenly it was all over and I found myself standing in a farmyard in Norfolk. And a scruffy one at that. So I resumed my walk and got soaked in a second shower.

Bromholm Priory, ruins of Chapter House.

(You can find out more about Bromholm Priory, a Cluniac monastery built in the 12th century and suppressed in the 16th century - together with a lovely little 3D model of it put together by The Paston Heritage Society - here .

I took the photos with a Hasselblad 500CM on Ilford FP4+ rated at 200 and developed in Ilford DDX. )